Indeed, Mac seemed to have formed his own model of the ideal ninja, and surprisingly enough it also included a certain amount of self-discipline. In the morning, he was shivering a bit as he struggled to get into his school clothes. Asking him if he was a bit chilly, he responded almost defiantly, “Ninja no cold!”

It took me a minute to figure out what he was saying, but eventually I was able to translate his expression into adult English – “Ninjas don’t get cold”. Cute little turn of phrase it was, making clear how fully he had taken on the role of a ninja. But the more I thought about it, the more I wondered if there wasn’t something else going on here –something remarkable in fact. I may be romanticizing a bit (grandparents are anything but impartial observers of their progeny of course!). But bear with me – it’s the idea that counts.

Let’s start by considering two fundamental questions – Where did Mac get the notion that ninjas don’t get cold? And what internal dynamics drove him to adopt this idea of ninja-hood so completely?

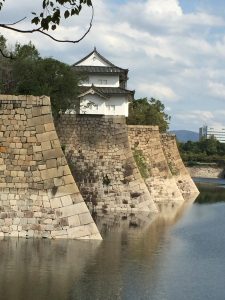

As to internal dynamics, the process of adopting such a persona (or “archetype” as Jung might call it) likely begins with an attraction to its external presentation – the strength and power, righteousness even, of the ninja characters he has seen. So he does what any child would do – imagines himself a ninja, practices his 3 ½ year old ninja moves in his imaginary dojo, and basks in the glow of a new personality that is both externally attractive and internally satisfying. Being a ninja, like being a knight in shining armor, a cowboy, or an astronaut, is doing a lot for him in terms of building a positive self-image.

But something else is going on too – the persona, once adopted, has started making demands on him as well. Shinobu is, in a small way, becoming part of his life as he adopts an age-appropriate level of self-discipline in his effort not to feel the cold that morning.

And this, if you think about it, represents a ray of hope as regards child development. There is a lot of hand wringing today about broken families, absent fathers, latchkey kids, and the impact all of this will have on society. I don’t want to downplay any of this – it is serious. We may already be seeing some of the consequences in our current chaos, and they are horrific.

Yet at the same time, we know that somehow there are children who manage to transcend difficult environments and emerge with a sound character and a personality that is intact. And Mac’s little story shows us one way in which this can happen – through the inspiration offered by positive and attractive images of the person they could become.

Shinobu is, in a small way, becoming part of his life as he adopts an age-appropriate level of self-discipline in his effort not to feel the cold that morning.

Offering a child such inspiration, through stories, books, or even (dare I say it?) films, is something you can do for any child you know, regardless of whether you are a parent, grandparent, aunt, uncle, teacher, or just a good friend. What their family or community may be unable to do for them in many cases, they just might be able to learn how to do for themselves.